|

|

You’re receiving the inaugural issue of Vested Interest, Wealthfront’s new, biweekly newsletter about what the latest developments in economics and finance might mean for your money, career, and life in general. Get in touch via askwealthfront@wealthfront.com with comments and questions about other topics you’d like us to cover.

|

|

|

|

- How Mr. Market is thinking about Venezuela and the Fed

- Rust Belt > Sun Belt (in one specific sense)

- Bajillion-dollar modern art is so back

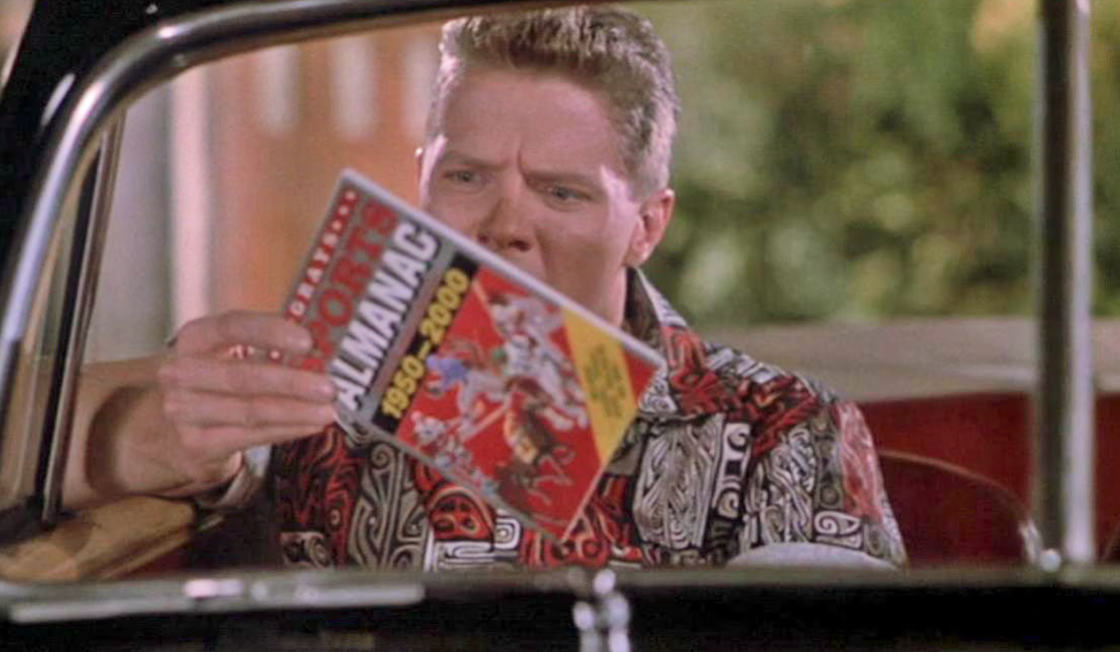

- Sports betting gets the asset class treatment

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Collateralized pigskin obligations, synthetic Cowboys default swaps, things of that nature?

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Three numbers that explain the economic moment.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3.64%

|

|

That’s the current “effective federal funds rate,” a measure of the cost of overnight interbank lending that provides a baseline for longer-term interest rates. It’s at the center of this week’s news that the Department of Justice has subpoenaed Federal Reserve Bank chair Jerome Powell over alleged misuse of taxpayer funds — which Powell says is payback for the Fed not lowering rates fast enough. The political and legal implications of this claim are outside the purview of this newsletter, and the White House denies Powell’s allegations. But investors care about Fed independence because historically, central banks that are co-opted by elected officials have often lowered rates so far that they trigger runaway inflation, which dilutes the value of assets. So far, though, the fear of such conditions has not led to a major sell-off — suggesting that the market collectively believes that legislators and other officials will protect the Fed’s independence until Powell’s term is up in May (and beyond).

|

|

|

|

$59.89

|

|

The price of a barrel of West Texas Intermediate crude oil as of publication time — not too far off a recent four-year low, and relevant to the relative lack of economic fallout from Nicolas Maduro’s ouster in Venezuela. The U.S. wants its domestic oil majors to get into the Venezuelan market, but with crude prices depressed, investing the funds required to boost production from the country’s aging infrastructure and refine its “heavy” oil is a tough ask. In other words, Venezuela wasn’t producing much oil to begin with, which is why recent developments haven’t created shortages and price surges globally — but no one is expecting to make much money there any time soon either.

|

|

|

|

The Rule of 40, The Rule of 80+, The Rule of 113, and The Rule of 114

|

The most relentlessly chewed-over question in finance right now is probably whether AI stocks are overvalued — and the mouthful of very specific “rules” above comes from a single paragraph written by Truist investment banker Arvind Ramnani to justify his continued “buy” recommendation for one of those stocks, the data processing company Palantir. Palantir’s share price has risen tenfold in the last two years, and it’s now one of the most valuable companies relative to its actual earnings in the S&P 500. As such, some industry skeptics deride it as a “meme stock” that’s outrunning its fundamentals because of cult-like attention from individual retail investors.

The phrase “Rule of 40,” meanwhile, originates in venture capital circles and holds that if a software company’s profit margins and year-over-year revenue growth add up to more than 40 when expressed as percentages, it’s a healthy business. Ramnani is observing that in recent quarters, Palantir’s growth rate and profit margin percentages have combined for sums as high as 113 and 114, which are not just way over 40, but way over 80. In other words, the company is getting bigger and making money; Ramnani was pushing back against critics who cite one potentially troubling Palantir metric (its high P/E ratio) by pointing to a more reassuring one.

Which number is more relevant to PLTR’s future? We don’t give investment advice on specific companies here, but we will say that not having to make judgment calls on questions like that one is one of the advantages of passive index investing.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

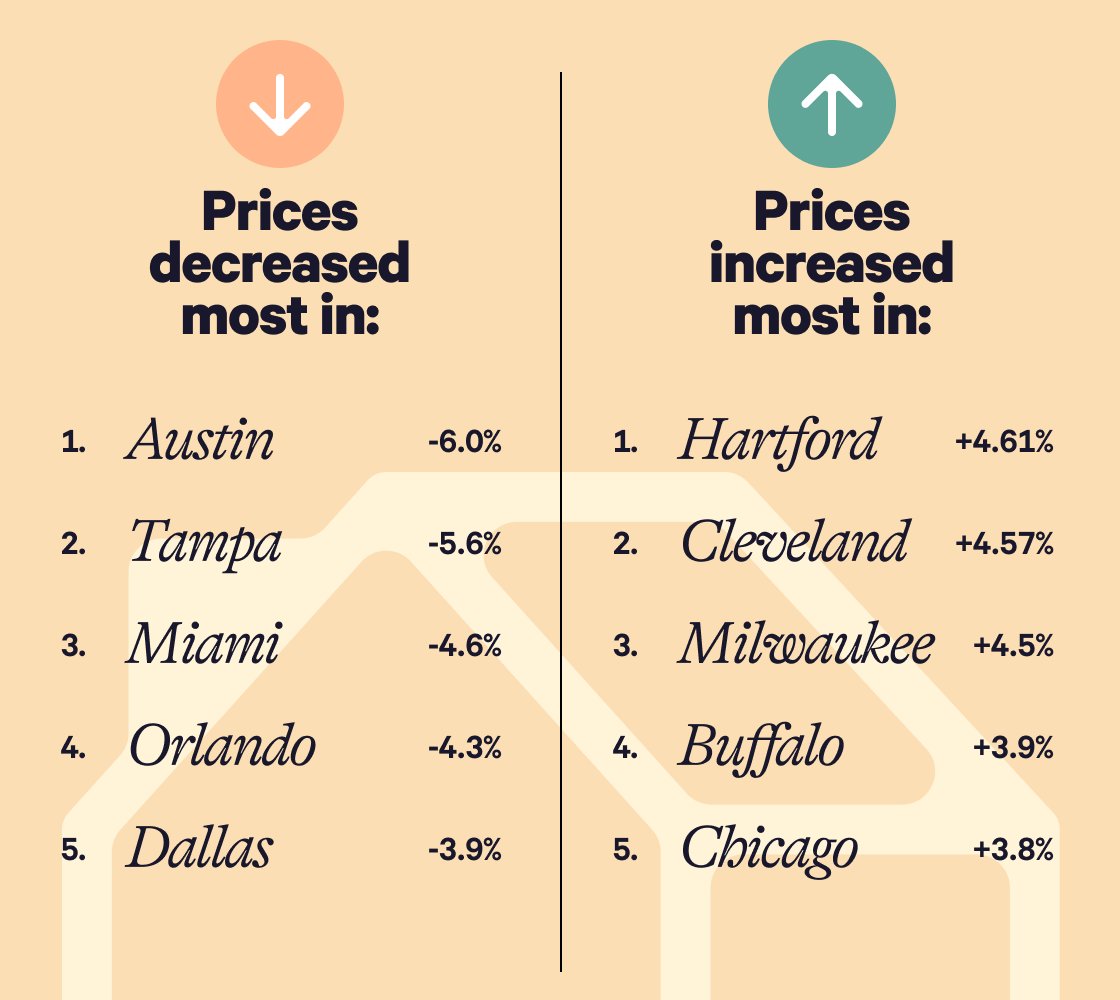

Where housing prices rose and fell the most in 2025.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: ResiClub analysis of YoY Zillow data for 50 largest metro areas.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Migration to the Southeast surged during and after the pandemic, driving up prices and triggering new construction. Now, though, states like Texas and Florida have too much inventory while buyers are competing for homes in the Midwest and Northeast that are still comparatively cheap. (Average sale price in Hartford: $189,744; average sale price in Austin: $489,253.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Automated Investing Account

Automated Investing Account

|

|

|

|

Serious investing made seriously simple

|

|

|

|

Investing doesn’t have to be scary or complicated. Starting with as little as $500, our Automated Investing Account makes it easy to begin your investing journey—no Ph.D. in Finance required.

|

|

Beat high-yield savings over time

Beat high-yield savings over time

|

Managed for you to keep things simple

Managed for you to keep things simple

|

The ideal way to learn how to invest

The ideal way to learn how to invest

|

|

|

Get started

|

|

|

|

|

|

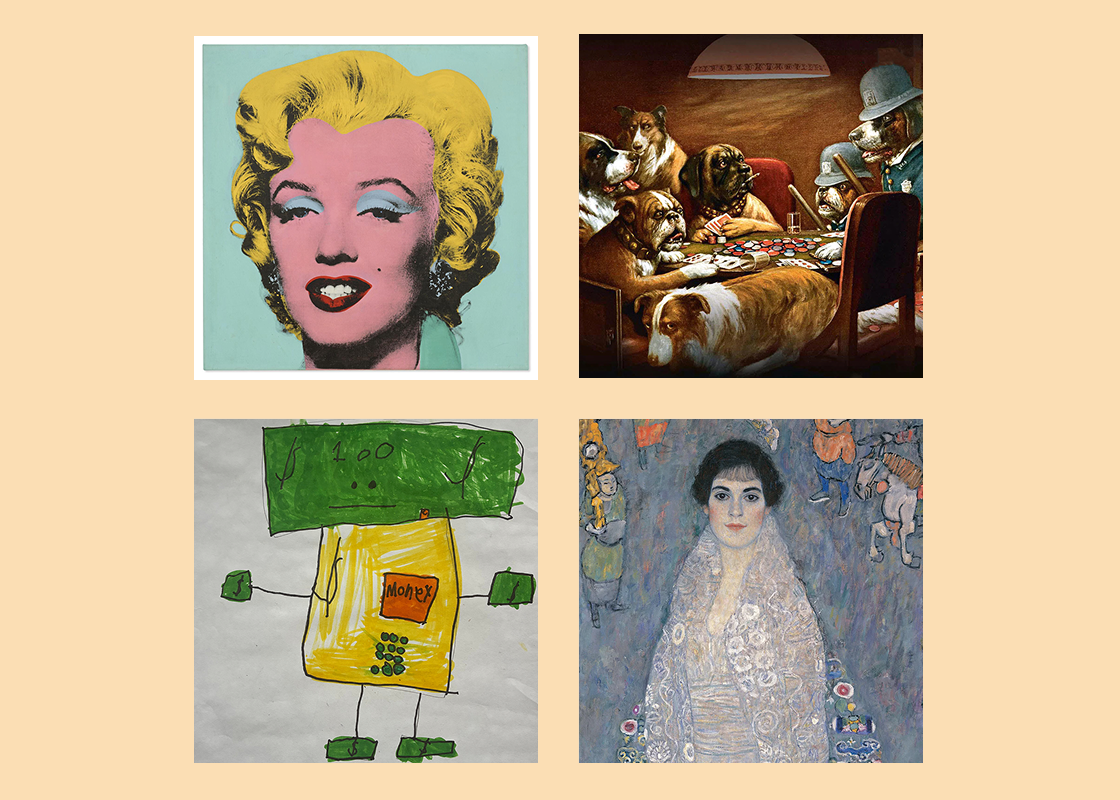

Which of these is now the most valuable work of modern art in history?

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

It’s the one in the lower right — Portrait of Elizabeth Lederer by Gustav Klimt, which recently sold for a record-breaking $236 million in New York City. (The other three, respectively, are Andy Warhol’s Shot Sage Blue Marilyn, American artist Cassius Marcellus Coolidge’s painting of dogs getting arrested by dog police officers for playing poker, and a robot made of money drawn by a Wealthfront staffer’s son when he was 7.) The art world hopes the sale is a sign of resurgence in a market that’s been experiencing a multi-year slump — a decline that observers have pinned on factors ranging from the chilling effects of tariff uncertainty to high interest rates, Millennial philistinism, and even war.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Is betting on sports an investment? “Prediction markets” would like you to think so.

|

|

|

|

|

|

With somewhat unnerving speed, betting on sports in the United States has gone from being a predominantly criminal activity to a legal, frictionless form of everyday entertainment. Now, according to some of its boosters, it’s even a form of investing. Open a “prediction market” app and you can buy “event contracts” that pay you, say, $100 if the Houston Rockets win their next game and $0 if they don’t. Which isn’t that different, advocates claim, from buying commodity futures.

It’s true that some kinds of speculative investing, like day-trading individual stocks, have long been compared to gambling. But do sports wagers really belong alongside index ETFs and bond ladders?

Philosophically speaking, economists like decorated financial researcher Ken French tend to say no, because betting on the New York Jets does not facilitate an economic purpose that adds value to the world. But it’s also a question you could approach empirically. And while betting companies are not typically forthcoming with information about their clients’ returns — perhaps there’s a lesson there! — it happens that the state of Illinois publishes monthly numbers on the amount that individuals within state borders are betting on sports and how much they’re getting paid back in winnings. Since January 2020, all told, this group has wagered about $47 billion online on professional sports and made $43 billion back, a net loss of 8.5%. (In the same time period, by comparison, the S&P 500 has gained 112.5% — although that number is, historically speaking, anomalously high.)

This result is not surprising: Sports books set odds with the goal of attracting roughly equal numbers of winners and losers for each bet, and then take sizable fees (the house’s cut, “vig,” “juice,” etc.) from the winners. There’s no way that gamblers, in total, can take out more than they put in.

Prediction markets, though, charge lower fees — for now — than sports books. And what if you were really good at predicting sports outcomes? Is there a potential edge at hand for a true ball-knower?

Leaving aside that research shows the average sports bettor is significantly worse at predicting winners and losers than they think they are, a paper published in 2025 in the Journal of Sports Analytics by University of North Florida professor B. Jay Coleman is informative. Coleman, who studies operations management and quantitative methods, evaluated the historical predictions made between 2016 and 2024 by 29 different college football team-ranking models and found the five most accurate. In a best-case scenario using the averaged predictions of these five systems to bet against the spread, Coleman told us, a hypothetical gambler could have won 51.5% of their bets over the nine years he studied.

Is that good? Well, even if you subtracted the relatively small 1.2 percent fee charged at the moment by one leading prediction market, it would come out to something like a 1.8% annualized return. That’s less than the current rate of inflation, and less than half of what you could have made last year, for instance, by putting cash in a money market fund. Over the past decade, even funds that hold short-term Treasury bills — which are some of the most conservative investment vehicles possible — have beaten our hypothetical best-on-Earth gambler, returning 2% on an annualized basis.

|

|

|

|

Put simply, getting a “return” by betting on sports is very tough.

|

|

|

That’s true, it seems, even if you have the best system around — and there’s no guarantee a historically successful system is going to keep working. The entity taking the other end of your “event contract” tomorrow — which could be a hedge fund, by the way — has the same access to past data that you do.

Psychological studies of sports betting, meanwhile, have found that such wagers are associated with “substantial overoptimism” and the release of neurotransmitters like dopamine. Think about it this way: Would you let someone else manage your money if they told you their investing philosophy revolved around neurochemical stimulation and the power of positive thinking? Even professionals have trouble consistently making correct predictions about companies and markets, which is why diversification exists. And while it might not be theoretically impossible that an individual working on their own could get better returns making predictions about sports, it is, as they say, a long shot.

|

|

|

|

|

|

# of mentions of AI in this issue 1

# of mentions of crypto in this issue 0

# of mentions of the New York Jets in this issue 1

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Wealthfront Corporation, 261 Hamilton Ave. Palo Alto, California, 94301, US

|

The information contained in this communication is provided for general informational purposes only, and should not be construed as investment or tax advice. Nothing in this communication should be construed as a solicitation, offer, or recommendation, to buy or sell any security. Any links provided to other server sites are offered as a matter of convenience and are not intended to imply that Wealthfront Advisers or its affiliates endorses, sponsors, promotes and/or is affiliated with the owners of or participants in those sites, or endorses any information contained on those sites, unless expressly stated otherwise.

Diversification and automated investing do not guarantee profit or ensure against loss. Investor experiences can vary widely based on strategies and time horizons. Index funds and ETFs generally offer broad diversification, but may still expose investors to specific market, sector, or asset class risks. Wealthfront provides investment management services but may not achieve returns comparable to those of the general market or specific benchmarks.

All investing involves risk, including the possible loss of money you invest, and past performance does not guarantee future performance. Please see our Full Disclosure for important details.

Investment management and advisory services are provided by Wealthfront Advisers LLC (“Wealthfront Advisers”), an SEC-registered investment adviser, and brokerage related products are provided by Wealthfront Brokerage LLC ("Wealthfront Brokerage"), a Member of FINRA/SIPC.

Wealthfront Advisers and Wealthfront Brokerage are wholly-owned subsidiaries of Wealthfront Corporation.

© 2026 Wealthfront Corporation. All rights reserved. | Privacy Policy

|

|

|

|